There has been much discussion about the lack of diversity in geoscience, but the statistics available mainly inform us about ethnicities in certain countries, and do not distinguish between different nationalities1,2. However, not all passports are created equal: nationality can greatly affect a geoscientist’s career and the opportunities available to them.

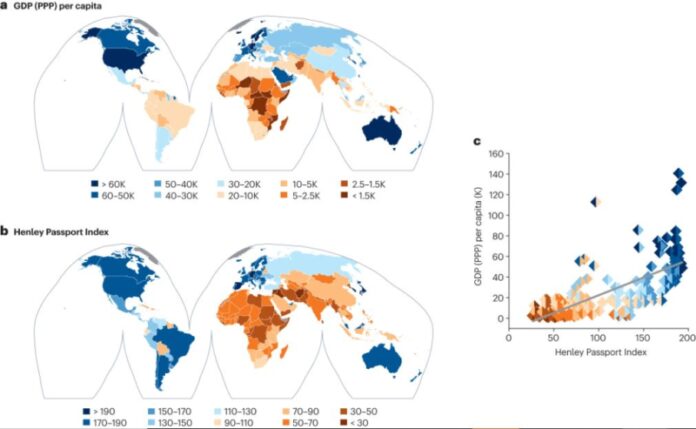

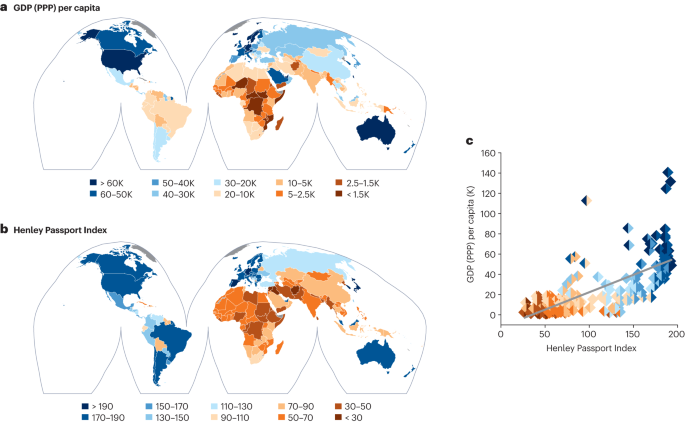

The unequal distribution of economic resources between the global north and south (Fig. 1a) limits the possibilities of pursuing a career in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) to a handful of high gross domestic product (GDP) countries. This has led to the ‘human capital flight’ phenomenon3, where scientists originating from countries with very low GDP per capita emigrate towards wealthier countries in search of career opportunities in STEM. Getting a study or work visa for a high GDP country can be a difficult, expensive and lengthy process, in which the hurdles faced depend on nationality4,5. Passport rankings (Fig. 1b), which measure the access power of nationality, are not commonly used as a parameter to measure the wealth of a country, but there is a clear correlation between passport rank and GDP per capita (Fig. 1c).

a, The gross domestic product GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita12 (US dollars), which is the GDP per capita index adjusted for the cost of living reported. b, The Henley passport index13 is the number of countries that can be visited visa-free with a particular passport. a,b, Countries with unavailable data are marked in grey. c, The correlation (0.70) and linear fit (grey line) between the GDP (PPP) per capita (left-side diamond) and the Henley passport index (right-side diamond) are reported.

Although the details vary by country, the limitations of some visas and resident permits offered to scientists with low rank passports, such as single-entry visas, can make these researchers vulnerable to academic bullying6,7. It can also prevent geoscientists with low rank passports from undertaking fieldwork for their research or attending certain conferences, and creates barriers for researchers with spouses and families, whether through physical separation or financial burden (for example, if a spouse is not permitted to work). Although some researchers may be able to reside long enough in a country to qualify for another nationality that could provide better systemic opportunities, short-term contracts and the emphasis on mobility as an asset in academia are in opposition to this.

Access to funding and financial support is strongly linked to citizenship. For example, many European institutions offer free or reduced tuition fees to students holding European passports, while other international students must either pay significantly larger fees themselves or find scholarships or loans from their own home countries. For countries that do not permit work while on student visas, this can exert a heavy financial toll. There can also be a disparity in the amount of funding available to scientists from different countries. Government-supported research may be restricted to citizens or those holding permanent resident status, and fewer grants exist that allow citizens of developing countries to apply. Individuals from developing countries with multiple nationalities, who are holders of a passport of a wealthy country, are more likely to emigrate and be able to obtain funding and low tuitions5, as well as having a support network outside their home country.

Citizens of countries with a low rank passport often have few job opportunities in their own countries3. While certain developing countries with oil resources can offer some job opportunities in geoscience research to their own citizens, other countries without oil or gas resources have limited investment in STEM8. Although such countries could be rich in other natural resources, geophysical surveys that could generate local jobs are often performed by scientists based at wealthy foreign institutions that may not include local experts as collaborators9. Furthermore, scientists from developing countries can be minorities even when doing science in their own home countries. For example, it was recently reported8 that only ∼10% of scientists working in Kenya in Paleontology and related fields had a local citizenship.

Beyond the more tangible issues, the fear and stress associated with the insecurity of visas, resident permits, employment and access to other types of support can take a toll on the mental health of international scientists. These stress sources were exacerbated by the recent COVID-19 pandemic10,11.

A geoscientist’s passport controls their career more than is currently acknowledged. Efforts to improve diversity and inclusion should also consider the barriers that nationality poses in the increasingly international field of geoscience. This is especially important since geoscientists with low ranked passports and from low GDP countries are often also visible ethnic minorities in the high GDP countries in which they study and work.